ETUC resolution on the European Union public debt issue and the fiscal rules

Adopted at the virtual Executive Committee Meeting of 5-6 October 2021

|

Executive summary and proposals • Debt sustainability analysis is heavily dependent on interest rates charged to EU Member States and their respective rates of growth. Although the outcome of the ECB review of its monetary policy is disappointing in this regard, since there is no mention on the future of its unconventional policies or the enlargement of its mandate, it cannot be neglected that monetary measures put in place in 2020 by the European Central Bank (ECB) de facto confirmed its commitment to stop any return to a sovereign-debt crisis, providing Member States margins of manoeuvre, from a fiscal standpoint (Part 1). • Furthermore, one can still expect low interest rates on sovereigns to remain low for a long period of time, and assess inflation as a temporary phenomenon, while it is argued that debt cancellation for sovereign bonds held at the ECB would not change the economic situation substantially (Part 2). Nonetheless, to maintain confidence in the economic fundamentals of EU Member States and avoid a double dip crisis and vicious circles, the economic policy, and especially the way fiscal policy is pursued at Member States level, plays a crucial role to maintain high levels of growth, while supporting debt sustainability. A reform of the EU fiscal rules is therefore not only necessary for the purpose of a short to medium term stabilisation of the economy. It is also of vital importance in order to finance the socio-ecological transformation of our economy, guaranteeing full employment, high quality jobs and just transitions. This position is proposing a set of new fiscal rules (Part 3) that would allow to counter the main deficiencies of the current rules, especially their procyclical character, while supporting economic stabilisation and debt sustainability. In particular, and without changing EU Treaties, nor debt transfer: • It supports Members States having their fiscal targets country-specific, with different adjustment paths; |

1. State of play

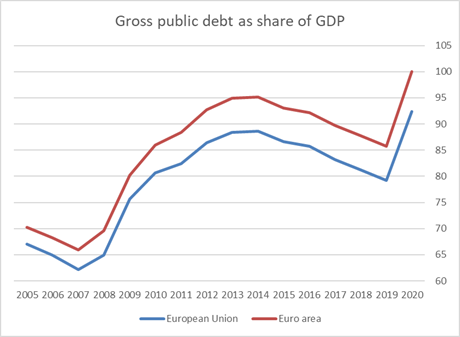

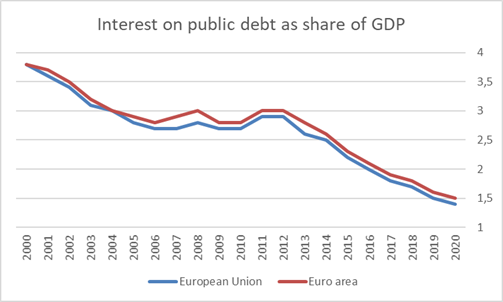

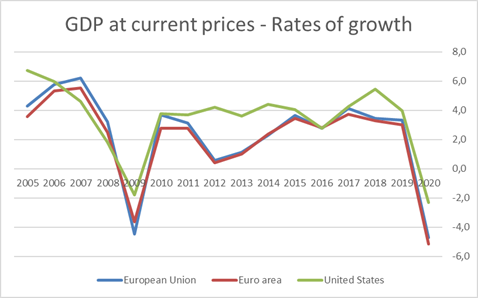

The massive impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the attempts to mitigate its social and economic effects have led to significant increases in government deficits and debt levels in a number of Member States. Consequently, debt to GDP ratios have increased very quickly, but interest charges as shares of GDP continued their decreasing trends, although GDP experienced a huge drop in 2020 (Figures 1 and 2).

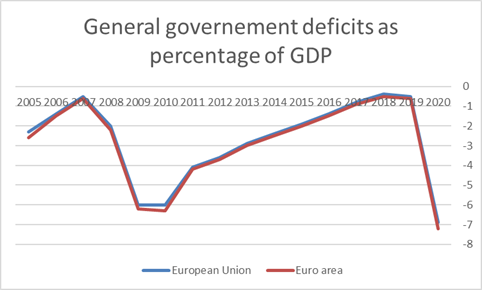

Therefore, public debt sustainability analysis must consider the additional charge for increasing nominal debt but also the benefits on GDP of increasing the nominal debt level. In other words, interest rates charged on sovereigns and the rates of growth are the two variables to be considered. Focusing too narrowly on debt to GDP ratios has two main shortfalls: it neglects the interest paid by Member States on their public debt, but also makes the implicit and fallacious assumptions that a decrease in deficits or even in nominal debt levels will necessarily mean a decrease in debt to GDP ratios, neglecting the effect a decrease in current deficits and future nominal debts have on growth (Figures 1 and 4).

In terms of public debt sustainability, a high debt to GDP ratio can be as safe/risky as a low one, depending on the design of monetary policy and the way fiscal policies are pursued. For example, the failure of governments to engage in debt-financed expenditure can result in a chronic lack of demand when the private sector is struggling. This in turn can raise unemployment and lower growth and inflation, endangering debt sustainability.

The ETUC adopted a position on the European Central Bank (ECB) Strategy Review with important requests, especially in relation to the mandate of the ECB[i]. The outcome of the ECB review is disappointing in this respect, just tweaking inflation target while committing to bolster its climate role. From an ETUC perspective, full employment should be put on par with the price stability mandate, while the European Parliament could use its annual resolutions on the ECB and its quarterly “monetary dialogues” hearings with the ECB to vote on top secondary objectives and develop a process that is more democratic with guidelines on macroeconomic and industrial policy. This would allow greater participation of social partners and citizens, along with national parliaments[ii]. Moreover, debt monetisation as a potential safeguard should not be rejected, as a matter of public debt sustainability. The ECB is a public institution and can be enlisted to help Member States to fund themselves in times of rising interest rates, either from price stability or employment perspectives[iii], by targeting interest rates and spreads and targeted monetary tools. Nonetheless, by adopting its emergency measures (especially the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP)) the ECB has de facto confirmed its commitment to stop any return to a sovereign-debt crisis. As a result, Member States can borrow at low rates of interest.

Ensuring public debt sustainability while providing the necessary financing for the socio-ecological transformation of our economies and just transitions paths, especially without the official support of monetary policy, lays with fiscal policy, and the effects of the fiscal rules on growth. And while a decrease in the debt to GDP ratios can be the goal to reach, the way to attain it is vital.

2. General considerations and the current fiscal framework

According to Blanchard & al. (2020)[iv] “interest rates in advanced economies in general, and in EU Member States in particular, are very low and expected to remain so for a long time. This has major implications for both national fiscal policy and EU level fiscal rules”. Low interest rates imply lower costs and lower risks associated with public debt. Also, low interest rates and constraints on monetary policy imply greater benefits from fiscal policy. However, arguments have been made that interest rates are kept artificially low by ECB monetary policy, and that this situation might not last as inflation could rise after the Covid crisis. While it remains undisputed that inflation plays a central role in ECB determination of its short-term interest rates and other unconventional monetary policy decisions, counterarguments can be raised making a lasting rise in sovereign interest rates a less likely scenario for the coming years. Finally, proposals for public debt held by the ECB and the European System of Central Banks cancellation have also been put forward, with questionable impact on economic activity.

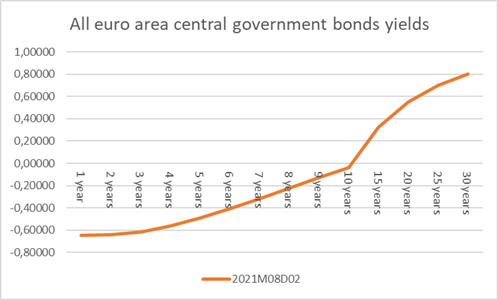

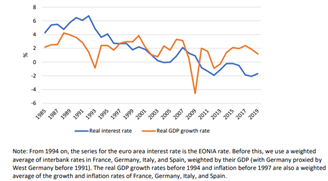

On interest rates

Nominal yields are currently negative over large portions of the yield curve for the euro area Member States as a whole (Figures 5) as aggregated by Eurostat. As of August 2021, German yields were negative for maturities up to 30 years, French yields for maturities up to 12 years, and Spanish yields for maturities up to 8 years, and Italian yields are below 1 percent for maturities up to 15 years and converge to less than 2 percent at 30 years[v]. In France, Germany, and Spain, nominal yields are way below the pessimistic forecasts of nominal growth over the medium term. However, the decrease in interest rates is not a new phenomenon. Figure 6, produced by Blanchard & al. (2020), in which the short-term nominal euro interest rate was extended back synthetically for the pre-euro period and deflated using consumer price inflation, shows that the decrease in interest rates started in the mid-1990s and continued throughout the financial crisis and its aftermath. Most forecasters expected rates to recover as the effects of the crisis decreased. In the euro area, this has not happened. The figure also shows that, since 2010, the (real) interest rate has remained lower than the (real) growth rate. Many reasons have been put forward to explain such a phenomenon, the first concerns negative shifts in investment and positive shifts in saving - caused by aging populations, a decrease in the relative price of investment goods, lower productivity growth, and higher inequality - both leading to lower equilibrium rates of return on capital and, by implication, lower rates on all assets[vi]. The second has emphasised an increased demand for safe assets – caused by slow post-crisis deleveraging, financial regulation, and higher demand for reserves by emerging market countries - leading to a decline in safe rates relative to returns on risky assets[vii]. And according to the authors, “Whatever the relevant combination, most of these underlying factors appear unlikely to turn around soon”.

On debt cancellation and inflation

When the ECB buys Member States bonds in the context of quantitative easing, it creates “seigniorage”. Member States then pay interest to the ECB, but the ECB returns this interest revenue to the Member States. Thus, when the ECB buys Member States bonds, Member States as a whole do not have to pay interest any longer on their outstanding bonds held by the Central Bank. A Central Bank’s purchase of government bonds is therefore equivalent to debt relief that is granted to a government. In this respect debt cancellation for bonds held by the ECB, will not imply substantial change[viii]. Indeed, if the ECB cancels that debt (i.e. set the value equal to zero), stopping the circular flow of interest payments, this would not make a difference on the burden of the debt. If the bonds that are kept by the ECB come to maturity, the ECB has promised it would buy new bonds to replace these, which makes no difference with outright cancellation. Consequently, as long as Member States bonds remain on the balance sheet of the ECB, it does not make a difference from an economic point of view at what value these bonds are recorded on the balance sheet of the Central Bank. It does not matter because the Member States bonds on the balance sheet of the ECB cease to exist. Moreover, as long as the money base is kept unchanged, the value given to the government bonds on the balance sheet of the central bank has no economic consequence. If these bonds were to be set equal to zero (debt cancellation) the counterpart on the liabilities side of the ECB would be a decline in equity (possibly becoming negative). But again, this is of no economic consequence. A Central Bank issuing fiat money does not need equity. The value of equity of a Central Bank only has an accounting existence. However, such a move could prove destabilising by questioning the safe asset character of Member States bonds.

Problems may arise if inflation surges and if the ECB wants to prevent the inflation to exceed 2%[ix]. However recent small spikes in sovereign interest rates stem from inflation expectations by market participants are unlikely to last. As stated by the ECB, the recent upswing in inflation in the euro area is due to idiosyncratic factors such as the end of temporary VAT rate reduction in Germany or higher energy price inflation[x]. Temporary, measured inflation is a plausible scenario in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis due to supply chain disruptions and pent-up demand for services. But over time as economies recover, these temporary effects have a low risk of leading to sustained or accelerating inflation. They should not be expected to overcome the structural drivers behind the decades-long fall in inflation rates[xi]. Moreover, assuming inflation rate would surge as a hypothetical consequence of a post-Covid recovery, major Central Banks have given indications that they could allow for some years a situation where inflation would exceed their usual 2% target without raising their key short-term interest rates while lowering the real cost of debts. The US Federal Reserve already stated this by adopting an average inflation targeting framework that allows for higher inflation offsetting prior underperformance[xii]. The ECB has made a similar move by recently adopting a symmetric 2% inflation target over medium term as part of its new monetary policy strategy[xiii]. In this respect, the ECB could keep Member States bonds on its books and roll them over when they come due, in effect becoming a regular buyer of Member States bonds, even when interest rates are above zero. The ECB could also actively manage long-term interest rates – similarly to what the Bank of Japan has done recently to raise growth and inflation, and what the US did after the World War II to keep funding costs of public debt low. One way to do so would be to cap long-term interest rates at a certain level, and buy as much government debt as is needed to maintain that cap. But this could be going a little too far. Finally, whereas in the USA the surge in inflation could be explained in view of for every 1% decline in GDP fiscal authorities allowed the budget deficit to increase by almost 2% of GDP and the Federal Reserve (Fed) bought approximately $2.6 trillion in government securities (compared to a 1% of GDP deficit increase and €1.3 trillion in the euro area, respectively); it is much less so in the euro area, where monetary and fiscal expansion does not appear to be hitting capacity constraints in the economy[xiv].

Problems with the current fiscal framework

Since before the crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the EU fiscal rules were in need of reform. The European Fiscal Board’s (2019)[xv] assessment of the EU fiscal framework rightly points out two of the main problems within the EU fiscal rules: the six-pack legislation and following changes have not reduced the procyclicality of fiscal policy and have not prevented severe cuts in public investment over the past decade in some Member States. It also identified multiple sources of unnecessary complexity, calling for a simplification of the existing fiscal framework.

Following the 2008/2009 financial crisis, Member States and EU institutions triggered some fiscal impulse but stopped fiscal support too early and implemented a new set of fiscal rules which did not produce the expected effects, leaving the European economy in a double-dip crisis. Fiscal tightening, which was a result of poor monetary policies, as early as 2010, has caused the sovereign debt crisis, aggravated by the implementation of a procyclical fiscal framework. S. Gechert & al (2017)[xvi] analysed whether there are negative (positive) long-term effects of austerity measures (stimulus measures) on growth. They found strong and persistent long-run multiplier effects for most European Member States in the early years after the financial crisis and the subsequent Eurozone crisis, concluding that early stimulus was beneficial even in the long run, while the subsequent turn to austerity was badly timed and thus deepened the crisis. Only when the European Commission interpreted and applied the rules in a more relaxed manner (European Commission (2015); European Council (2015))[xvii], together with the ECB’s willingness (declared in 2012) to provide guarantees for the government bonds under stress, was a partial economic recovery possible, although through very much export-oriented economic patterns, reinforcing the existing imbalances within the euro area, and leaving the EU in a very dependent geopolitical position.

Indeed, since, contrary to households, cuts in (public) spending greatly affect (public) revenue, the European (and euro area) debt to GDP ratio increased until 2014, instead of decreasing, as expected by some. In the US the Central Bank is both mandated with price stability and maximum employment. It was able to launch quantitative easing as early as 2010, deficit reduction was less abrupt, thus preventing a double-dip crisis. It allowed to stabilise the public debt to GDP ratio, while allowing a decrease in interest payment as share of GDP. Total hours of work in the US began to increase in 2010 and reached its pre-crisis level in 2014, while a slight recovery in total hours worked took place only in late 2013 in the EU (and euro area) to reach pre-crisis levels in late 2018. Finally, public investment in the EU was the first target for spending cuts, impeding future economic development in a much more brutal manner than in other economies. Comparing the average government investment rate of 2015-2019 with the pre-crisis average (2005-2009) 20 out of 27 Member States saw their rate decline, for some by as much as 50%[xviii], to such an extent that the value of the stock of public capital, marked by negative net public investment, deteriorated between 2013 and 2017 in the euro area. In other words, the EU tackled the crisis in a very orthodox manner, by cutting spending at the expense of growth, very much counting on external demand at the expense of aggregate internal demand, while also leading to increased divergences in the economic performances of Member States[xix].

It is therefore clear that a return of fiscal tightening would not be sustainable economically, socially, or politically. Moreover, debt sustainability analysis, considering both interest rates on sovereigns and expected rates of growth, show that Member States could run larger deficits while either stabilising or decreasing debt to GDP ratios. There is therefore room for manoeuvre for expansionary fiscal policies, especially regarding public investment, while guaranteeing public debt sustainability and ensuring decisions are taken more democratically and transparently[xx]. The mistakes of the past must, but most surely cannot, be repeated. Namely, austerity policies followed in the aftermath of the last economic crisis have led to weakened and less resilient public services and further pressure on essential workers that have played a vital role to mitigate the COVID-19 sanitary crisis and its social impact.

The ETUC continues to oppose the fiscal compact[xxi]. The ETUC recalls that a social dimension of the economic governance needs a change in the fundamental rules of the economic governance. Art. 148 of TFEU is a weak counterbalance to the strength that the Treaty injects in the fiscal, market and macroeconomic components of the economic governance. It must therefore be revised to include the EPSR[xxii], if possible, in the Conference on the Future of Europe[xxiii].

3.The new fiscal rules

To respond quickly, effectively and in a coordinated manner, to this fast-evolving crisis, the European Commission activated the general escape clause introduced as part of the “Six-Pack” reform of the Stability and Growth Pact in 2011. Since the recovery will be uneven within the EU, the deactivation of the general escape clause and the implementation of a new fiscal framework within the European Union’s Members States should be gradual and conditional upon health and the social and economic situation across Member States, in order to ensure that fiscal support is provided for as long as needed.

Estimations by the European Fiscal Board (2020)[xxiv] show that if unchanged EU fiscal rules were activated after lifting the general escape clause, the foreseen debt ratio reduction path would overburden some Members States, with significant negative economic, social and political consequences, risking the economic recovery in the EU. Indeed, the debt reduction rule would have an even stronger procyclical effect than it already had before the pandemic. It could lead to turbulences in the sovereign bonds’ markets, destabilising the common currency. Thus, a one-size fits all prescription for debt ratios' reduction path is no longer tenable nor acceptable.

A reform of the EU fiscal rules is not only necessary for the purpose of a short to medium term stabilisation of the economy. It is also of vital importance in order to finance the socio-ecological transformation of our economy, guaranteeing full employment, high quality jobs and just transitions. It should give equal weight to a range of key policy objectives such as sustainable and inclusive growth, full employment, decent work and just transitions, fair distribution of income and wealth, public health and quality of life, environmental sustainability, financial market stability, price stability, well-balanced trade relations, a competitive social market economy and sustainable public finances. This would be consistent with both the objectives set out in Article 3 on the Treaty on the European Union and with the current UN Sustainable Development Goals.

To achieve the EU climate targets, a profound modernisation of the capital stock is needed. This entails a massive expansion of public investments. In previous positions, the ETUC has already underlined the need to introduce a golden rule for public investment in the EU fiscal framework[xxv]. The ETUC recalls that public investment should not be seen as a cost but as a source of future revenue. These demands remain valid: for Europe to meet its 2030 climate and environmental targets, the European Commission recently estimated the overall funding gap to be around EUR 470 billion a year until 2030[xxvi]. As rightly emphasised “mobilising the necessary scale of finance will be a significant policy challenge”, and clearly public investment will have a critical role to play, not least also in order to trigger private investment. The reform of the EU fiscal framework has to take these considerations into account.

Finally, both the IMF[xxvii] and the European Commission[xxviii] state that debt to GDP ratios should stabilise in the short to medium term, thanks to low interest rates and increased growth rates. We urge the European Commission to take these factors into consideration when assessing Member States debt sustainability.

Strengthening public investment

The EU fiscal framework needs to be reformed in a way to better protect public investments. The multiplier effect of public investment is particularly high, and cuts in public investment, therefore, have a particularly negative impact on economic growth and employment. Cuts in public investment, and in government spending more generally, are particularly damaging in times of economic slumps and recessions[xxix]. In addition, many studies also identify public investment as a growth booster in the long term[xxx]. A long-term increase of public investments also provides a more secure basis for private sector planning[xxxi].

These facts justify an approach that treats public investments preferentially as far as the assessment of Member States compliance with EU fiscal rules is concerned. The ETUC continues to advocate a golden rule for public investments, to safeguard productivity and the social and ecological base for the well-being of future generations. In general, the ETUC suggests implementing the traditional public finance concept of the golden rule within the revised fiscal framework [xxxii]. This means that net public investments, as defined in the national accounts, need to be excluded from the calculation of the headline deficits. If an expenditure rule is implemented as demanded (see below) net public investments should also be excluded from the public expenditure ceiling, while investment costs would be distributed over the entire service-life, instead of a four-year period, as it is currently the case. Net public investment increases the public and/or social capital stock and provides benefits for future generations. Future generations inherit the servicing of the public debt, but in exchange, they receive an increased public capital stock.

As a very first step, the ETUC suggests that “investment clause” of the Stability and Growth Pact should be interpreted more broadly. So far, it has been rarely invoked primarily because of its restrictive eligibility criteria[xxxiii]. These eligibility criteria should be broadened, and public investments should justify a temporary deviation from the adjustment paths, independently of the position of the Member State in the economic cycle and even if these investments lead to an excess over the 3% of GDP deficit reference value. Currently, deviations from the Medium-Term Budgetary Objective (MTO) or the adjustment path towards it are only allowed if they are linked to national expenditure on projects co-funded by the EU.

But more generally, the ETUC suggests a broader definition of public investments. The European Commission’s guidance to Member States in the context of the Recovery and Resilience Facility and the definition of investments therein constitutes a good starting point[xxxiv], as it includes investments in tangible assets but also investments in health, social protection, education and training, and investments aiming at the green and digital transition. At the very least, investment projects financed by the Recovery and Resilience Facility should be included in this list.

Reforming cyclical adjustment methods

The ETUC suggests reconsidering the European Commission’s method for cyclical adjustment. The current procedure is opaque, and a source of procyclicality[xxxv]. The European Commission’s method determining the structural balance has proven to be problematic because the calculated potential output is strongly influenced by the current economic situation. In phases of economic downturns, for example, potential output is quickly and sharply revised downwards, although this does not reflect real conditions[xxxvi]. The downward revision of potential output has severe consequences on the calculated structural deficit and the consolidation efforts identified respectively. Making the calculation of the potential output less sensitive to cyclical fluctuations can open up fiscal room for Member States for countercyclical economic policies.

Two alternative proposals could be considered. One option would be to use medium-term averages for potential growth or to revise potential output estimates only in the medium term, e.g. every five years. Such a potential calculation that is less sensitive to cyclical fluctuations would have suspended the potential adjustment from spring 2010 onwards and could have opened up considerable room for manoeuvre for all member states under the preventive arm of the SGP[xxxvii]. Another option would be averaging several potential output estimates[xxxviii] or integrating hysteresis effects[xxxix].

Flexible and country-specific debt adjustment paths & expenditure rule

The ETUC supports the proposal made by the European Fiscal Board (2020) to introduce country-specific elements in a simplified fiscal framework. In particular, the ETUC welcomes the suggestion regarding the differentiation of the fiscal adjustments in the Member States, while maintaining debt sustainability. A country-differentiation of debt to GDP reduction strategies should be based on a comprehensive economic analysis taking into account factors such as: the initial level of debt and its composition; the interest rate-growth differentials as a matter of sustainability; inflation perspectives; the projected costs of ageing and environmental challenges; unemployment and poverty levels; internal and external imbalances; and, primarily, whether the fiscal adjustment is realistic[xl]. It is of upmost importance to develop country-specific plans that enable Member States to effectively manage their public spending and investment over the long-term bearing in mind a broad range of economic, social and environmental factors.

The ETUC is critical about debt and deficit ratios targets that are set in the Protocol on the excessive deficit procedure annex to the Treaty, which could however be changed by a unanimous vote in the Council without a formal Treaty change procedure. Since such a process could prove to be problematic, the ETUC suggests fixing quantitative criteria in secondary law while allowing for regular revisions and country-specific deficit and debt ratios targets (adjustment paths), taking into account the current macroeconomic context.

The ETUC suggests abandoning the contested concepts of structural deficit/balance and instead implement a public expenditure rule in a revised fiscal framework[xli]. It is widely accepted that the change in the structural balance is a problematic indicator for the orientation of fiscal policy since it considerably underestimates the extent of fiscal restraint in phases of crisis and overestimates the success of consolidation during an upswing[xlii]. Unlike the cyclically adjusted deficit, public expenditures are observable in real time and are directly controlled by the government. Public investment should be favoured by separating current and investment budgets submitting only the current budget to limits for nominal expenditure growth. This way, the golden rule approach could be combined with an expenditure rule.

Nominal public expenditures would be calculated net of interest payments, of unemployment spending and spending related to minimum incomes schemes, and of the estimated impact of any new discretionary revenue measures, especially since particularly urgent measures required to address the substantial staff shortages in health and social care and the related problem of low wages in these sectors. The limits could be determined by the medium-term growth rate of real potential output plus the ECB target inflation rate of 2%. Increases in permanent nominal expenditure growth above this limit would be allowed if revenues are increased correspondingly. Such a rule would stabilise expenditure growth over the cycle and enable full implementation of automatic stabilisers[xliii].

Finally, within this context it is worth adding, that relying solely on national automatic stabilisers in recessions, is not fully in line with the idea of countercyclical policy. Fiscal deficits caused by reduced output and employment do not fully compensate cyclical losses and are not enough to fully counter a cyclical downturn. They are only passive and partial countercyclical responses and need to be supplemented by active discretionary temporary responses to cyclical downfalls to be reversed in upswings[xliv]. In the past, Member States had decided to continue decreasing debt to GDP ratios with negative economic consequences while fiscal stimuluses would have been more adequate[xlv]. In a future fiscal framework, provided that a favourable interest rate environment continues to prevail, larger primary deficits should be allowed, while keeping debt to GDP ratios constant and ensuring debt sustainability. This is why exceptional clauses must remain a cornerstone of any future EU fiscal framework and should be adapted accordingly.

Deactivation of the escape clause

The ETUC welcomed the activation of the fiscal framework's general escape clause and supports the European Commission’s decision to continue applying the general escape clause until 2022. However, the deactivation of the clause in 2023 should only happen if new system of economic governance is in place, the level of economic activity and unemployment rate reach the pre-crisis level[xlvi], while a broad assessment of the extent to which a sustained and sustainable economic recovery is underway, taking account of key social indicators, would be relevant. The ETUC supports the European Commission’s assertion that “country-specific situations will continue to be taken into account after the deactivation of the general escape clause”[xlvii].

Nonetheless, the ETUC demands a new and revised EU fiscal framework, following the main lines described above and asks the Commission to put forward country-specific guidelines for transition periods until its full implementation, during which time no excessive deficit procedure should be activated and with the possibility to use the ‘unusual event clause’ on a country specific basis.

4. Fiscal capacity and EU own resources

The ETUC, in various positions[xlviii], stressed that enhanced European fiscal capacity is key for the proper management of the EMU and that common countercyclical economic policy is needed to underpin countercyclical policies at national level.

In this position the ETUC expresses support to the increase of own resources ceiling, from 1.20% to 1.40% of the EU GNI, while a temporary increase in the ceiling, amounting to a further 0.60% of EU GNI, will be devoted exclusively to borrowing operations for NGEU[xlix]. The ETUC also supports the Interinstitutional agreement between the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission on budgetary discipline, on cooperation in budgetary matters and on sound financial management, as well as on new own resources, including a roadmap towards the introduction of new own resources[l]. Finally, the ETUC is urging for an agreement at the international level on tax avoidance taking place within the OECD/G20 Inclusive framework and could provide support[li] to the European Communication to the European Parliament and the Council on Business Taxation for the 21st Century[lii].

However, the ETUC, in consistence with the ECB stating that the EMU still lacks a permanent fiscal capacity at supranational level for macroeconomic stabilisation in deep crises[liii], and the European Fiscal Board (2020), calls for a permanent central fiscal capacity at the European level, allowing the European debt to be rolled over, paying interest, repaying old debts and issuing new ones, which would alleviate Member States’ contributions to the EU budget without debt transfers.

The failure to engage in debt-financed investments, be it at Member State or European level, can result in a chronic lack of aggregate demand when the private sector is struggling. This can raise unemployment and lower growth and inflation. Moreover, low public debt contributes to the global shortage of safe assets, leaving investors with fewer ways to safely store money in liquid assets. Finally, there is a huge demand for safe assets around the world[liv]. Safe assets play a crucial economic role. Some investors seek high, risky returns, but many just want a safe place to store their wealth. In addition, banks are mandated through regulation to hold safe assets, calling for larger increases in European safe assets. Low public debt contributes to the global shortage of safe assets, leaving investors with fewer ways to safely store money in liquid assets, putting at risk financial stability.

Figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Real interest rate and real GDP growth rate euro area

Notes

[i] ETUC position on the European Central Bank Strategy Review, adopted at the virtual Executive Committee Meeting of 9-10 December 2020.

[ii] P. Béres, G. Claeys, N. De Boer, P.O. Demetriades, S. Diessner, S. Jourdan, J. Van T Klooster & V. Schmidt (2021), “The ECB needs political guidance on secondary objectives”, Bruegel; V. Schmidt (2021), “Decentralising and democratising while reforming European economic governance”, Social Europe.

[iii] C. Odendahl & A. Tooze (2021), “Learning to live with debt”, Centre for European Reform.

[iv] O. Blanchard, Á. Leandro & J. Zettelmeyer (2020), “Revisiting the EU fiscal framework in an era of low interest rates”.

[v] World Government Bonds database.

[vi] L. Rachel & L. H. Summers (2019), “On Falling Neutral Real Rates, Fiscal Policy, and the Risk of Secular Stagnation”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. BPEA Conference Drafts, March 7–8. Washington: Brookings Institution; C. Odendahl & A. Tooze (2021), “Learning to live with debt”, Centre for European Reform.

[vii] See P.-O. Gourinchas & H. Rey (2019), “Global Real Rates: A Secular Approach”, BIS Working Paper n° 793. Basel: Bank for International Settlements and C. Odendahl & A. Tooze (2021), “Learning to live with debt”, Centre for European Reform.

[viii] P. De Grauwe (2021), “Debt cancellation by the ECB: Does it make a difference?”, LSE European Politics and Policy.

[ix] P. De Grauwe (2021), “Inflation risk?”, Intereconomics, Vol. 56, n° 4.

[x] C. Lagarde and L. de Guindos (2011) “Introductory statement to the press conference”, 11 March, ECB. However, although month-to-month inflation shows a return to pre-pandemic level, energy prices are still picking and could become structurally higher. In this respect, any future policy should be designed to avoid energy poverty as well as any other regressive distributional effect on low-income households.

[xi] R. A. Auer & al., “Low-wage import competition, inflationary pressure, and industry dynamics in Europe”, European Economic Review, Elsevier, vol. 59(C); K. Forbes (2019), “Has globalization changed the inflation process?”, Bank for International Settlements.

[xii] J. H. Powell (2020), “New Economic Challenges and the Fed’s Monetary Policy Review”, speech at the Jackson Hole annual conference.

[xiii] “The ECB’s monetary policy strategy statement”, July 2021.

[xiv] P. De Grauwe (2021), “Inflation risks?”, Intereconomics, Vol. 56, n°4.

[xv] European Fiscal Board (2019): “Assessment of EU fiscal rules. With a focus on six and two-pack legislation”.

[xvi] S.Gechert, G.Horn & C.Paetz (2017), “long-term effects of fiscal stimulus and austerity in Europe”, Working Paper n°179, IMK, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung.

[xvii] Respectively European Commission (2015), “Making the Best Use of the Flexibility within the Existing Rules of the Stability and Growth Pact”, COM (2015) 12 final; European Council (2015), “Commonly Agreed Position on Flexibility in the Stability and Growth Pact”, 14345/15 ECOFIN 888 UEM 422.

[xviii] European Fiscal Board (2019): “Assessment of EU fiscal rules. With a focus on six and two-pack legislation”.

[xix] Benchmarking Working Europe 2019, ETUI; M. Mascherini., M. Bisello, H. Dubois & F.F. Eiffe (2018), “Upward convergence in the EU: concepts, measurements and indicators”, Publications Office of the European Union.

[xx] ETUC resolution on a new EU Economic and Social Governance, adopted at the virtual Executive Committee Meeting of 3-4 June 2021.

[xxi] ETUC Action Programme 2019-2023, Vianna, May 2019.

[xxii] ETUC Resolution on a new EU Economic and Social Governance, adopted by the Executive Committee, 4-5 June 2021.

[xxiii] Priorities for the activities of the ETUC in the Conference on the Future of Europe.

[xxiv] European Fiscal Board (2020), Annual Report.

[xxv] ETUC Position Paper: A European Treasury for Public Investment Adopted at the ETUC Executive Committee on 15-16 March 2017.

[xxvi] Commission Staff Working Document (2020), “Identifying Europe's recovery needs - Identifying Europe’s recovery needs”, SWD (2020) 98 final.

[xxvii] “Favourable interest–growth differentials and projected fiscal adjustment plans—likely to occur at a faster pace than projected before the pandemic— are expected to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratios in most advanced economies over the medium term”, in IMF Fiscal Monitor Reports, April 2021.

[xxviii] “Importantly, such interventions [i.e ECB policy], together with decisive EU actions in 2020 [i.e SURE, NGEU/RRF and the ESM PCS], contributed to stabilising sovereign financing conditions, lessening risks of short-term fiscal stress”; “Favourable snowball effects should allow a progressive reduction of the aggregate debt ratio, despite primary deficits (…) favourable interest rate – growth rate differentials (snowball effects) are expected to more than compensate the positive contribution from the primary deficits towards the end of the projection period, and allow a progressive reduction of the debt ratio.”, in Debt Sustainability Monitor, European Commission, February 2021.

[xxix] European Commission (2016), “Report on Public Finances in EMU 2016”, Institutional Paper No 045; J.-M. Fournier (2016), “The positive effect of public investment on potential growth” OECD Economics Department, Working Paper No. 1347.

[xxx] IMF Fiscal Monitor (2020), Policies for the Recovery.

[xxxi] H. Bardt, S. Dullien, M. Hüther & K. Rietzler (2020), “For a sound fiscal policy. Enabling public investments“, IW policy paper No 6/2020, Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft (IW), Köln.

[xxxii] A. Truger (2020), “Reforming EU Fiscal Rules: More Leeway, Investment Orientation and Democratic Coordination”, Intereconomics, 55(5); N. Álvarez, G. Feigl, N. Koratzanis, M. Marterbauer, C. Mathieu, T. McDonnell, L. Pennacchi, C. Pierros, H. Sterdyniak, A. Truger, J. Uxó (2019), “Towards a progressive EMU fiscal governance”, Working Paper 13, ETUI.

[xxxiii] J. Valero (2019), “New investment clause fails to win EU member state support”, Euractiv; European Commission (2015), “Making the best use of the flexibility within the existing rules of the stability and growth pact”, COM (2015) final.

[xxxiv] European Commission (2021), “Guidance to Member States. Recovery and resilience plans”, SWD (2021) 12 final, part 2/2.

[xxxv] P. Heimberger & J.Kepeller (2017), “The performativity of potential output: pro-cyclicality and path dependency in coordinating European fiscal policies”, Review of International Political Economy.

[xxxvi] A. Truger (2015), “Austerity, cyclical adjustment and the remaining leeway for expansionary fiscal policies within the current EU fiscal framework”, Journal for a Progressive Economy, 6, 32-37; Z. Darvas, P. Martin & X. Ragot (2018), “European fiscal rules require a major overhaul”, Policy Contribution, Issue n˚18, Bruegel.

[xxxvii] A. Truger (2020), “Reforming EU Fiscal Rules: More Leeway, Investment Orientation and Democratic Coordination”, Intereconomics, 55(5).

[xxxviii] C. Fontanari, A. Palumbo & C. Salvatori (2019), “Potential Output in Theory and Practice: A Revision and Update of Okun’s Original Method”, Working Paper No. 93, INET.

[xxxix] A. Fatas (2019), “Fiscal policy, potential output, and the shifting goalposts”, IMF Economic Review, 67(3), 684-702.

[xl] European Fiscal Board (2020).

[xli]Z. Darvas, P. Martin & X. Ragot (2018); S. Dullien, C. Patz, A. Watt & S. Watzka (2020), “Proposals for a reform of the EU’s fiscal rules and economic governance”, IMK report 159e.

[xlii] Z. Darvas (2019), “Why structural balances should be scrapped from EU fiscal rules”, Blog Post, Bruegel.

[xliii] “In a background work to this study, we found, using average revision values in 2010-2018, that the budget balance implications of structural balance revisions is more than 5-times larger than that of the medium-term potential growth rate revisions”, in Z. Darvas & J. Anderson (2020), “New life for an old framework: redesigning the European Union's expenditure and golden fiscal rules”, European Parliament.

[xliv] J. Priewe (2021), “Reforming the fiscal rulebook for the euro area – and the challenge of old and new public debt”, Study n° 72, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung.

[xlv]P. De Grauwe & Y. Ji (2019), “Rethinking fiscal policy choices in the euro area”, VoxEU CEPR.

[xlvi] European Commission (2021): “Economic policy coordination in 2021: overcoming COVID 19, supporting the recovery and modernising our economy”. COM (2021) 500 final.

[xlvii] European Commission (2021): “One year since the outbreak of Covid-19: fiscal policy response”, COM (2021) 105 final.

[xlviii] ETUC Position Paper: A European Treasury for Public Investment Adopted at the ETUC Executive Committee on 15-16 March 2017; ETUC Position Paper: Reflection paper on the Deepening of the Economic and Monetary Union – ETUC assessment, adopted at the ETUC Executive Committee on 13-14 June 2017; ETUC Position Paper: Assessment of the EMU package, adopted at the ETUC Executive Committee on 13-14 December 2017.

[xlix] European Council, Conclusions (EUCO 10/20), 21 July 2020

[l] Interinstitutional Agreement of 16 December 2020 between the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission on budgetary discipline, on cooperation in budgetary matters and on sound financial management, as well as on new own resources, including a roadmap towards the introduction of new own resources.

[li] Additional research should be devoted on the proposals regarding new tax incentive related to equity financing and companies’ carry back losses which could lead to new loopholes in the corporate tax system.

[lii] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, Business Taxation for the 21st Century, COM (2021) 251 final.

[liii] A. Giovannini, S. Hauptmeier, N. Leiner-Killinger & V. Valenta (2020), “The fiscal implications of the EU’s recovery package”, ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 6/2020; C. Look (2020), “Lagarde Urges EU to Consider Recovery Fund as Permanent Tool”, Bloomberg.

[liv] On 18 May 2021, the European Commission issued the seventh social bond under the EU SURE which was over 6 times oversubscribed; C. Odendahl & A. Tooze (2021), “Learning to live with debt”, Centre for European Reform.